Perhaps this story is familiar to you…

Your team has been tasked with designing and building a groundbreaking software product that focuses on putting the end user — the person who will use the product — at the center of the design and development process. The stakeholders want it delivered within 12 months.

Six months into the project, the hunger for innovative, user-centered features seems to wane.

The delivery team adopts a rapid agile cadence that values predictable delivery dates and velocity rather than experimentation to find the best solution for the user.

The design team attempts to get ahead of development in order to ensure user insights lead the build of new features. Unfortunately, priorities shift after each deployment, and much of that work gets thrown away.

Over time, a chasm forms between user-centered advocates and delivery. Their ideas are just too risky and unpredictable for the mission: get the next release out the door.

An all too familiar tale, but with an ending we can change. I think there is a way to get the most out of the user-centered design and Agile processes while keeping to budgets, timelines, and a consistent delivery cycles.

First, though, why is this tale all too familiar?

A bias towards reliability and predictability

We’re naturally inclined to have a bias towards reliability, predictability and reducing risk. And Agile development does this by design.

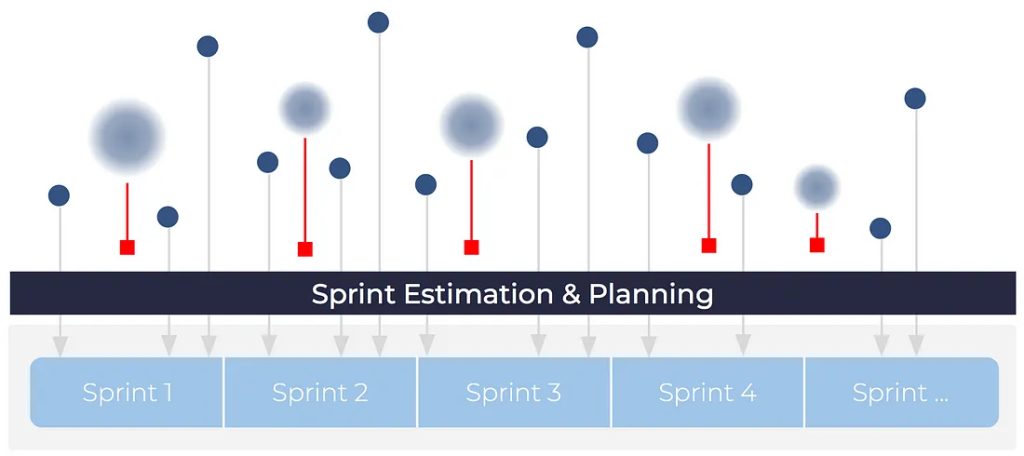

The sprint-based nature of Agile development makes its output extremely predictable — yielding releases every couple of weeks. But it works best when requirements are understood upfront and can be accurately estimated.

However, teams often overestimate new features and unfamiliar technical challenges to account for the delivery uncertainty. This results in teams prioritizing the most predictable features over the most innovative ones.

In contrast, user-centered design focuses on the people who will use the software, and how they can easily and efficiently achieve their goals. It leverages primary research — actually getting insights and feedback from future users — to discover previously unknown friction points in the user experience. It seeds the invention of new experiences that offer that far better way.

While some of the ideas that come from this process can offer a 10x improvement in the experience, they are also unproven and often unfettered by technical and business process constraints. The discovery-driven nature of the process makes the output impossible to predict.

An incompatible match

The issue is that user-centered design and Agile development are incompatible.

- User-centered design aims for maximal astonishment — let’s see if our users can tell us something we didn’t know.

- Agile aims for minimal astonishment — let’s have as few surprises in our development process as possible.

To steal a concept from physics, user-centered design prioritizes voltage — a measure of potential energy. Agile development prioritizes amperage — a measure of the flow of current.

And in the same way that you wouldn’t want to plug your TV into a high-voltage power line, the friction between Agile and user-centered design comes when you directly connect the two methodologies.

While the results might be less spectacular than an exploding TV, the failures are just as predictable:

- Innovative ideas lag development timelines and create project delays.

- Innovative ideas get chopped in favor of timelines.

- Through long hours, a talented team squeezes in a couple of extra features deemed “top priority.”

In all three cases, the drive for innovation eventually wanes:

- Unmet delivery promises undermine organizational and investor trust in the team’s ability.

- Continuous cutting of new ideas demoralizes the team into a “good enough” mentality and opens up questions about the ROI of exploring innovative ideas to begin with.

- Unsustainable hours create organizational churn and the talent carrying the greatest load walk out the door.

Still in order to successfully invent new user-centered solutions AND deliver them, we need the strength of both. We need a way to convert the high potential energy output of user-centered design into the high current that the Agile process demands.

Treat user-centered design as investigation, not validation

User-centered design is a process that requires a lack of preconceptions and an open mind. The goal is to understand the root causes of user behavior in order to formulate a new, better approach. Keeping a hypothetical solution in mind through the process creates a cycle that reinforces our original assumptions and often blinds us to other opportunities.

So, when a request comes in to “redesign an app,” start by abstracting that request into the underlying goals that the user accomplishes while using the app. Then, use primary research to validate that those goals are real and dig into how they are accomplished today. You may learn that users don’t care about what you think they do. You might also learn that an app isn’t even the right enabler for their goal.

At the end of this process, you will get a list of things to build that will improve the user’s experience. They just might not be the ones you expected.

Only feed de-risked features into the Agile process

In order to keep the Agile delivery process moving efficiently, ensure that any proposed features/stories are well understood both in terms of their requirements as well as their technical complexity.

Before ever estimating a feature, you should know:

- That implementing the feature will generally increase user perception of the experience

- The way to solve any key technical or data hurdles

- Confidently, how long the feature will take to build

If a feature doesn’t meet all of those criteria, then it could easily derail the predictability that is the key benefit of Agile development.

De-risking features enables teams to estimate without fear because the basic how of implementation is already well understood.

Use experimentation to connect user-centered design and Agile

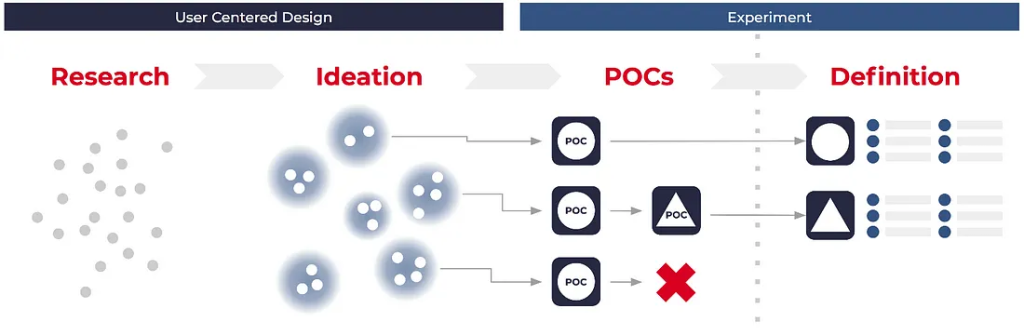

The un-vetted output of user-centered design makes it a poor input into an Agile process that works best with low risk requirements. To bridge the two, we need an intermediary process that takes fledgling ideas and systematically de-risks, prioritizes and roadmaps them at a program level.

This middle phase — experimentation — acts as the glue.

Prototype, test and rapidly iterate on proof of concepts (POCs) with users to ensure that your features will have the desired impact on the user experience. These experiments provide a view into the potential ROI. By providing a clearer picture into the new experience, they also can generate investment interest at the executive level.

Similarly, technology experiments (often referred to as technical design spikes) can be used to de-risk complex technical and data problems. In this phase, the priority is not delivering a minimum viable product. Instead, the goal is taking the riskiest assumption and exploring the solution space.

At the end of experimentation, these pre-vetted features can be fully story-mapped and prioritized for delivery — the perfect input to the Agile delivery phase.

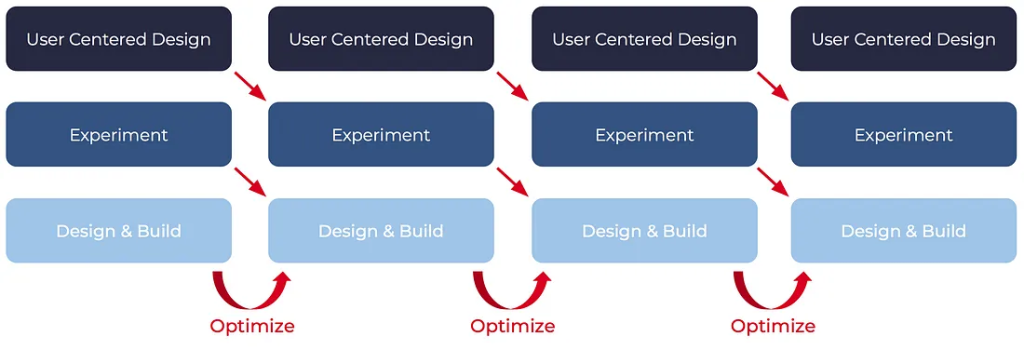

Run all three phases concurrently as an innovation program

While the experimentation phase ensures compatibility between user-centered design and Agile, it is important to note that these methods run at different speeds.

- User-centered design takes a long time to conduct, but yields a high volume of opportunities.

- Experimentation can be done quickly but the output may or may not produce viable results.

- Agile generates small chunks of production-ready functionality at a regular pace.

To keep all processes operating at full speed, allow each of these phases to run independently and concurrently over time. Each phase generates a queue of work for the next. User-entered design creates a queue of experiments. At the same time, experimentation creates a queue of user-vetted, de-risked features for implementation.

With a never-ending list of to-dos in all three work streams, the program will operate at full efficiency. And innovative, user-centered features will flow like clockwork into your products and experiences.

Tyler Klein is the Executive Experience Director at Robots and Pencils. Physics major turned HCI specialist, he uses what’s new to build what’s next and offers far better ways to interact with the world around us. Special thanks to Chris Chew, Jamie Reid, Mike Greening, Reid Sheppard and Aaron Slepecky for their contributions.